Plato’s Dialogue #2: Apology

(Sorry, not sorry.)

Socrates is sorry…that his accusers are wrong. In this dialogue, he responds to the charges against him, suggests a light sentence, and contemplates the nature of death. We’ll cover it all! (This is a follow-up to my first blog, Let’s Talk About Socrates.)

Want to read Plato’s Apology for yourself? You can find it free at your local library, or read Plato’s Apology free online here:

http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/apology.html

The Case Against Socrates

How sophisticated would you expect a legal argument to be in 399 B.C.? How civilized do you envision Ancient Athens to be? If you’re a historian, you already know the answer: very — but as an ordinary American, I was amazed to read Socrates’ eloquent words to the citizen court of 501 jurors responsible for deciding his fate. He speaks thoughtfully, calmly and convincingly as he addresses each accusation against him.

I should not have been surprised that Socrates was such a good speaker, or that the courts in Athens were so advanced. After all, Athens is the birthplace of democracy. The word “democracy” comes from the Greek words “demos,” meaning “the people,” and “kratos,” meaning power—and Athens had already been holding citizen assemblies for 195 years before Socrates came to trial, so the Athenians knew what they were doing.

Derevyagin Igor, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Sorry, I’m Old

Socrates begins his Apology by apologizing for his age (over 70) and his inexperience in court, and essentially asks the jurors to bear with him. We talked about his accusations in the last blog, which focused on Euthyphro, but in Apology, Socrates addresses his accusers more directly, and examines why he is being accused.

Sorry You’re Wrong

One accusation is that “Socrates is an evil-doer, and a curious person, who searches into things under the earth and in heaven, and he makes the worse appear the better cause; and he teaches the aforesaid doctrines to others.” To this charge, Socrates says, “I have nothing to do with physical speculations.” He was not a teacher of natural science, so this part of the accusation is inaccurate.

As to curiosity, no one could deny that Socrates enjoys asking questions, but since when does curiosity equate with evil? I think Socrates makes a very good point when he worries that those who hear this accusation “are apt to fancy that such inquirers do not believe in the existence of gods.” Science and religion are often at odds, but I’m with Socrates on this: these things don’t have to be mutually exclusive. You can be curious about the world and have questions about religion, while still believing in God. I know I do.

One person who damaged Socrates’s reputation is Aristophanes, a comic poet who portrayed Socrates as an obnoxious character who spoke nonsense and misled young people in his play, Clouds. What did Socrates do to piss off Aristophanes so badly that the playwright would slander him? Socrates spells it out for us quite clearly in Apology.

By Nicolas-André Monsiau - http://www.newacropol.ru/pub/Petrozavodsk/Lectoriy/Socrates.jpeg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30954997

Sorry I Got on Your Nerves

To summarize the philosopher’s explanation, Socrates annoyed a lot of people by asking them questions to test their wisdom, and pointing out that they were, in fact, not very wise. He usually did this in front of an audience, which made the inquiries even more embarrassing. To make things worse, Socrates tended to question individuals who had power and reputations to uphold, including poets, politicians and artisans. Why did he do it? Because he wanted to learn the meaning of a prophecy made by the famous Oracle of Delphi, a priestess who inhaled fumes from a fissure in the Earth, and then spoke on behalf of the gods. Don’t give up on me yet, things are just starting to get interesting.

By John Collier - Art Gallery of South Australia Website Webpage PictureOld source [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1077695

The Oracle Says I’m Smarter than You

So, what happened was, Socrates’s friend Chaerephon had visited the Oracle of Delphi and asked if there was any man wiser than Socrates. The Oracle said no. Socrates, who had always proclaimed that he knew nothing, then set out to see whether he could find a man who was truly wise, and bring him to the Oracle to refute the god who said he was the wisest.

“What can the god mean? And what is the interpretation of his riddle?” Socrates asks. “I know that I have no wisdom, small or great. What then can he mean when he says that I am the wisest of men? And yet he is a god, and cannot lie; that would be against his nature.”

So he decides to go out and see if he can find a man wiser than himself, so that he can bring such a man to the Oracle to refute her claim. He starts with a politician who is “thought wise by many, and still wiser by himself.” Good one, Socrates. I see politicians haven’t changed that much over the past 2,422 years.

He questioned the politician and came away thinking that the politician was not truly wise. He did the same with poets and artisans, and while he admitted that they knew many things he did not, they thought they knew things that they did not actually know. Socrates concludes that he himself is wiser because he knows that there are some things he does not know.

By Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg - [1] Archived 2016-03-07 at the Wayback Machine; [2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33098705

I am Wise Because I Know Nothing

“I am better off than he is, for he knows nothing, and thinks that he knows; I neither know nor think that I know,” Socrates says. “I am called wise, for my hearers always imagine that I myself possess the wisdom which I find wanting in others: but the truth is, O men of Athens, that God only is wise; and by his answer he intends to show that the wisdom of men is worth little or nothing...He, O men, is the wisest who, like Socrates, knows that his wisdom is in truth worth nothing.” This makes me feel a bit better about myself.

Sorry Your Kids Think I’m Cool

In addition to frustrating the politicians, poets and artists in Athens, Socrates has also frustrated the older generation in general. This is because young, wealthy men who have nothing better to do often follow Socrates around and listen to his inquisitions. They think it’s a lark, so they try it out themselves. Try to imagine a bunch of teenagers who think they know everything, proving that you don’t know anything. It’s not very hard to imagine.

Of course, these whippersnappers were likely even more annoying than Socrates, and probably caused him to earn his reputation for corrupting the youth.

Nope, Not an Atheist

At this point in the dialogue, Socrates brings up Meletus, one of his accusers, and begins to question him, putting his method on display. He challenges Meletus on several points, and to my mind, the most salient is the inherent contradiction in Socrates’s charges. Meletus says that Socrates is an atheist who invents new gods, or demigods. Well, which is it? If he’s an atheist, he doesn’t believe in any gods, so why invent new ones? At any rate, Socrates claims neither of these accusations are true.

Next, Socrates makes a moving speech about how he will not back down from philosophy, which he feels is a calling from God, even if it leads to his death. (Spoiler Alert #1: It will.)

By (Athenians against Corinthians, 431 BC; Socrates saves Alcibiades).Engraving (sketch) by Wilhelm Müller after the drawing, 1788, by Jakob Asmus Carstens (1754–1798). From: H.Riegel, Carstens Werke, 2nd ed., Leipzig 1869. Berlin, Sammlung Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte. - AKG Images, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75905226

How Could They Find Him Guilty After This Amazing Speech?

Socrates had served in the Peloponnesian War, and he points out that he had always remained where his general placed him, without fearing death, because it was his duty as a soldier. In the same way that he served his General and his country, he will also serve God and philosophy. Socrates will not leave his post as a philosopher just because it may lead to his death. He truly feels that God wants him to pursue wisdom. It is what he must do. He also believes he does good to others by encouraging them to better their souls. Wasn’t he right? We are still reading his words today. I am so glad Socrates stuck to his guns.

I think this section also speaks to Socrates’s skill in understanding his audience. His reference to honor and serving one’s country would have connected deeply with the Athenian audience, who revered honor as one of the cardinal virtues. I imagine it would resonate with an American audience, too—we have great respect for our veterans. I should note that before he talks about his own military service, he reminds the audience about how Achilles avenged Patroclus by killing Hector in the Iliad, without any fear of death. The Iliad was the closest the ancient Greeks had to a Bible. How better to sway the hearts of men than a nod to God and Country? Surely this approach would work. (Spoiler Alert #2: It didn’t work.)

Honestly, I would quote the entire passage if I thought you guys would read it, but for some reason nobody but me seems to be reading Plato for fun, so I’m going to share a few lines to entice you:

“For the fear of death is indeed the pretense of wisdom, and not real wisdom, being a pretense of knowing the unknown; and no one knows whether death, which men in their fear apprehend to be the greatest evil, may not be the greatest good.”

Here's another good line, and something I wonder about a lot. Just replace “Athens” with “Plano.”

“O my friend, why do you who are a citizen of the great and mighty and wise city of Athens, care so much about laying up the greatest amount of money and honor and reputation, and so little about wisdom and truth and the greatest improvement of the soul, which you never regard or heed at all?”

Why don’t more people think about wisdom and philosophy and the betterment of the soul? Present company excluded, obviously. If you’re actually reading this, I take it you’re a seeker. Socrates believes he is serving God by practicing philosophy.

“I do nothing but go about persuading you all, old and young alike, not to take thought for your persons and your properties, but first and chiefly to care about the greatest improvement of the soul,” he says.

He says that if he is killed, the people of Athens will be injuring themselves more than they injure him.

“For the evil of unjustly taking away the life of another—is greater far. And now, Athenians, I am not going to argue for my own sake, as you may think, but for yours, that you may not sin against the God by condemning me, who am his gift to you.”

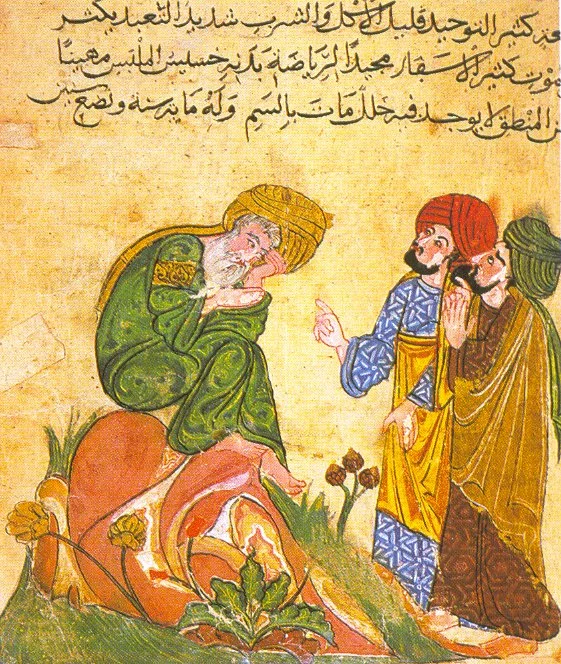

By Al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik - From English Wikipedia: en:Image:Arastu.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=435623

God’s Gift to Athens

Wait a minute, did Socrates just say he’s God’s gift to us? I think he did. Well, I’m grateful God gave us Socrates. It’s been 2,422 years and we’re still talking about what he had to say. Socrates goes on to say that if they do kill him, he will not be easily replaced, for he is like a gadfly, constantly awakening men…and they wish he would go away so that they could go back to sleep. But he is not doing this for money. His poverty, he says, is evidence of this. He is doing it because he believes it is God’s will.

It gets even more interesting as he tells us about the voice in his head that tells him what not to do, but never commands him. A Jiminy Cricket, of sorts. This voice, which we might call conscience, kept him out of politics. He tells how he once served as a senator, and declined to vote with the majority because he thought their ruling was unjust.

“Now do you really imagine that I could have survived all these years, if I had led a public life, supposing that like a good man I had always supported the right and had made justice, as I ought, the first thing? No, indeed, men of Athens, neither I nor any other.”

What a conundrum—we need ethical, moral people to serve in public office, but oftentimes the most ethical people are attacked when they follow their conscience. It’s so much easier to go with the flow, and follow the Party.

Room Service to the Prytaneum, Please

Wrapping things up, the jury finds Socrates guilty and condemns him to death. Tough crowd.

There is one part here that cracks me up. After the guilty vote is read, but before the sentence of death, Socrates suggests his own sentence: The City should put him up in the Prytaneum, a kind of town hall where foreign ambassadors and respected citizens were entertained, and take care of him there. Why not? He hasn’t really done anything wrong. They decline. Well, it was worth a try.

By Sting, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=96296061

Death to Socrates

Following the death sentence, Socrates admonishes:

“Not much time will be gained, O Athenians, in return for the evil name which you will get from the detractors of the city, who will say that you killed Socrates, a wise man; for they will call me wise even although I am not wise when they want to reproach you. If you had waited a little while, your desire would have been fulfilled in the course of nature. For I am far advanced in years, as you may perceive, and not far from death.”

Socrates prophesies to his accusers that a worse fate awaits them than the punishment they have inflicted upon him (they will be judged for killing Socrates). Then he invites his friends to stay and chat with him for a while, which they do. In fact, they’ll try to bust him out. We’ll read about their plans in the next blog, which will summarize Plato’s Crito.

No Fear of Death

Before I close this blog, I have to share one more nugget of wisdom, and Socrates has saved the best for last. I apologize, but I just have to quote this whole section because it is exquisite. I’ve bolded the best parts:

“Let us reflect in another way, and we shall see that there is great reason to hope that death is a good, for one of two things: - either death is a state of nothingness and utter unconsciousness, or, as men say, there is a change and migration of the soul from this world to another. Now if you suppose that there is no consciousness, but a sleep like the sleep of him who is undisturbed even by the sight of dreams, death will be an unspeakable gain. For if a person were to select the night in which his sleep was undisturbed even by dreams, and were to compare with this the other days and nights of his life, and then were to tell us how many days and nights he had passed in the course of his life better and more pleasantly than this one, I think that any man, I will not say a private man, but even the great king, will not find many such days or nights, when compared with the others. Now if death is like this, I say that to die is gain; for eternity is then only a single night.

But if death is the journey to another place, and there, as men say, all the dead are, what good, O my friends and judges, can be greater than this? If indeed when the pilgrim arrives in the world below, he is delivered from the professors of justice in this world, and finds the true judges who are said to give judgment there, Minos and Rhadamanthus and Aeacus and Triptolemus, and other sons of God who were righteous in their own life, that pilgrimage will be worth making. What would not a man give if he might converse with Orpheus and Musaeus and Hesiod and Homer? Nay, if this be true, let me die again and again.

I, too, shall have a wonderful interest in a place where I can converse with Palamedes, and Ajax the son of Telamon, and other heroes of old, who have suffered death through an unjust judgment; and there will be no small pleasure, as I think, in comparing my own sufferings with theirs. Above all, I shall be able to continue my search into true and false knowledge; as in this world, so also in that; I shall find out who is wise, and who pretends to be wise, and is not. What would not a man give, O judges, to be able to examine the leader of the great Trojan expedition; or Odysseus or Sisyphus, or numberless others, men and women too! What infinite delight would there be in conversing with them and asking them questions! For in that world they do not put a man to death for this; certainly not. For besides being happier in that world than in this, they will be immortal, if what is said is true.”

I happened to be reading Plato after my mom died in 2016, and this passage gave me so much comfort. When you think about death this way, it really removes a lot of the fear. Imagining the conversations you can have with everyone who has gone before you…what a joy. I don’t know about y’all, but when I die, I hope I get to speak to Socrates.